Comparing verbosity bias in Human and LLM based evaluators

Much has been reported recently about biases in LLM based evaluators - for instance, LLM’s have been reported to exhibit position bias favoring options in earlier positions over others [1] [2] [3], verbosity bias favoring more verbose outputs [4], diversity bias favoring outputs using higher number of distinct tokens, and bias towards LLM-based outputs [5]. These have often been used as a critique of such approaches. In addition, the most common method of validating automated metrics is their correlation with human judgement. It’s worthwhile, then, to ask the question: Do humans suffer from the same biases?

In this micro-post, I dig into the verbosity bias on four popular benchmarks: The first, a task of miscellaneous prompts from the MT-bench [4] dataset. MT-bench contains 3.3K pairwise human preferences on model outputs from 6 strongly performing large language models - GPT-4, GPT-3.5, Claud-v1, Vicuna-13B, Alpaca-13B, and LLaMA-13B, which have been annotated for preference by graduate students with expertise on 8 topics (writing, roleplay, extraction, reasoning, math, coding, STEM, humanities/social science). A second similar task of miscellaneous prompts using the Vicuna benchmark [7] on competing models - Bard, Guanaco-7/13/33/65b, Vicuna-13b, GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and annotated for pairwise comparisons by Amazon Mechanical Turk workers. In a similar vein, human annotations on AlpacaEval prompts (~650 instructions each with 4 human annotations) on the GPT-4, Claude, Text-Davinci-003, ChatGPT-Functions, Guanaco-33b, and Chat-GPT models [8] [9]. Finally, a news summarization task/benchmark, using a dataset of preferences over LLM generated summaries and high-quality summaries for news articles written by freelance writers [6]. A reasonable hypothesis is that while humans (and LLMs) might lean towards verbosity in descriptive tasks, brevity is a reasonable preference of a summarization task.

Experiments exploring verbosity bias in human and LLM evals

LLM’s have been found to favor longer, more verbose responses, compared to shorter alternatives.

In order to examine verbosity bias, we first tokenize (by simply splitting-on-space) the text, and compute the length of tokens in the winning generated outputs. In cases of a tie in the evaluation, we randomly select one of the model outputs as winner for computing its token length. A binary flag is set to record when a longer winning token length is preferred over a losing token length.

On MT-Bench prompts

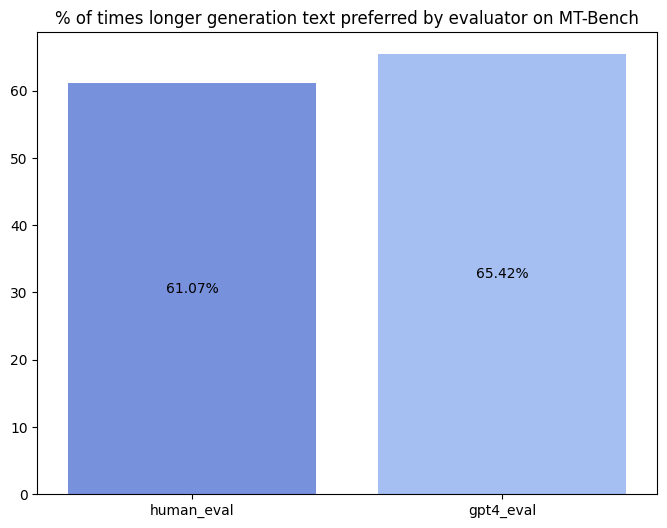

We compare the model generated outputs in MT-bench evaluated by human experts and GPT-4, and find that the rate of preferring longer generated text outputs is nearly the same by both, while being slightly higher for GPT-4 (Human eval - 61.22% versus GPT-4 eval - 65.95%). In most cases, it is natural to assume that longer generations convey more information or are perceived as better, but this may not necessarily be accurate.

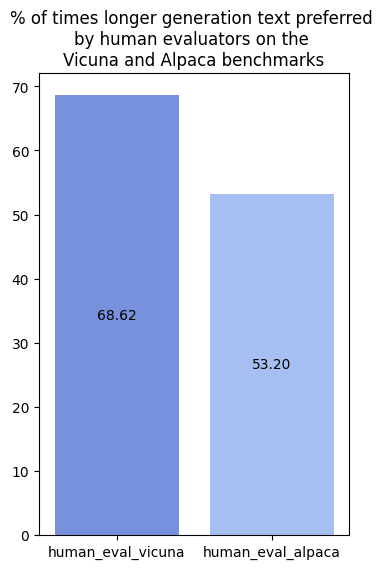

Similarly, on the Vicuna benchmark, 68.82% of the time, annotators preferred outputs with longer generations, between competing models (controlled for position bias). The bias is much lower on AlpacaEval, where the authors have noted such human biases, and appear to therefore more consciously address for these. This can been observed in the prompt instructions, where some specifically instruct for brevity; for instance “The sentence you are given might be too wordy, complicated, or unclear. Rewrite the sentence and make your writing clearer by keeping it concise…and eliminate unnecessary words…”

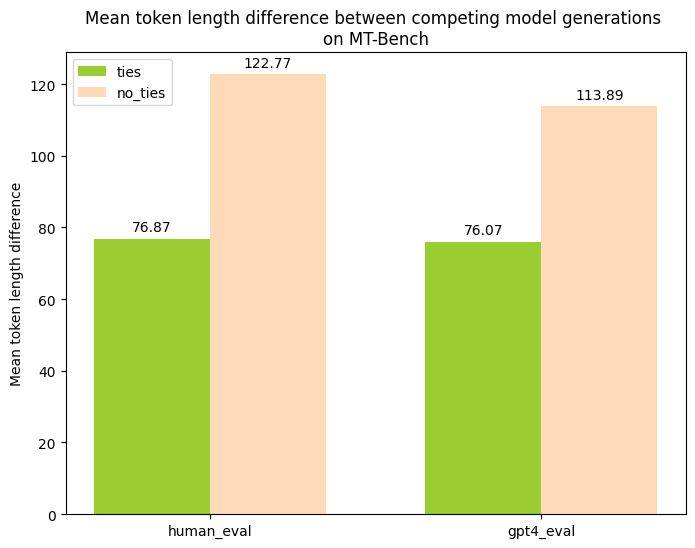

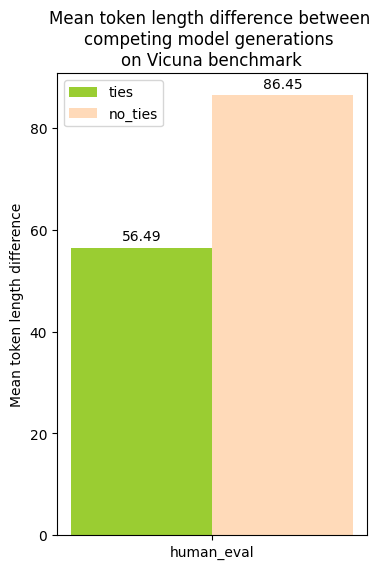

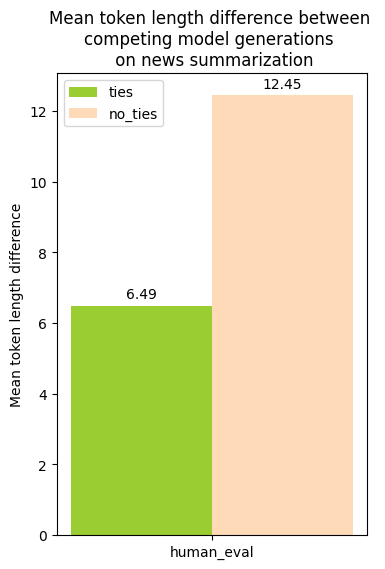

Between outputs that were marked as ties (between the two competing models), and those that were not ties (strict preference of one or the other model), I found that ties had a lower average token length difference between the model outputs, but that this behavior was similar to both human and LLM evaluations.

(AlpacaEval human annotations do not contain any instances of ties)

When I described verbosity bias above, I left out some parts that are used in its definition in the MT-bench paper - “even if they are not as clear, high-quality, or accurate”, mainly because I think the inductive bias towards longer outputs itself may exist without this distinction, and more importantly, because I do not think there have been sufficient studies to show that this is the case.

For example, MT-Bench creates an artificial “repetitive attack” task where a list of n items containing the answers are extended to 2n by paraphrasing the existing n items, artificially inflating it. Only GPT-4 is capable of sustaining this attack, while Claude-v1 and GPT-3.5 favor the longer list outputs. While this task is an interesting one, it is not reflective of a typical output of current strongly performing models, and is perhaps less useful in a real-world benchmark.

Intuitively, it’s easy to see how descriptive and creative tasks such as “Compose an engaging travel blog post about a recent trip to Hawaii, highlighting cultural experiences and must-see attractions” or “Describe a vivid and unique character, using strong imagery and creative language. Please answer in fewer than two paragraphs” would prefer longer outputs over more concise ones.

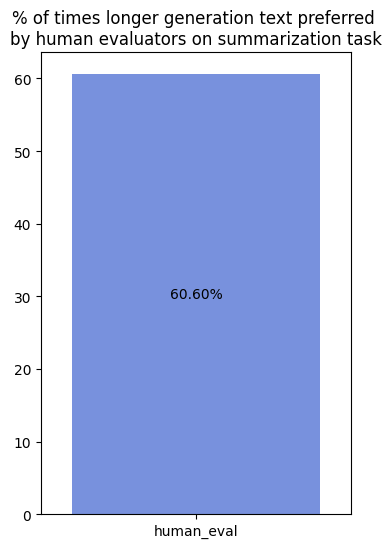

On a News Summarization task

We look at the task of news summarization, where, one would expect a preference of concise outputs over more verbose ones. However, on the news summarization dataset, we find that the same pattern as above holds, with longer “overall” summaries being preferred over shorter ones (Human eval - 60.76%), even when the task is to prefer an “overall better summary” (i.e. when not judging for “a more informative summary”).

Discussion and Conclusion

If such known biases exist in human evaluations, it begs the question if the underlying task creation needs to be adjusted to first debias it. For instance, on both the general and summarization tasks, could they have included specific instructions that guide the annotators against these known biases, or if the outputs were first controlled for length.

Human evaluations have been used as the gold standard on most NLP tasks, including recent benchmarks on LLMs. They have additionally been used in the creation of new metrics (including metrics using LLMs (a.k.a GPT-scorers), where a high correlation of a metric with human judgement is used to validate its reliability as a metric.

Even in the most basic case, as more and more studies are being published on the effectiveness (or non-effectiveness) of LLM-evaluators, analyzing their biases against human evaluators may help us understand where they come from.

If you use this post in your research, please consider citing as follows:

@article{amanda2023verbositybiasllms,

title={Comparing verbosity bias in Human and LLM based evaluators},

author={Amanda Dsouza},

year={2023}

}

References

[1] Miyoung Ko, Jinhyuk Lee, Hyunjae Kim, Gangwoo Kim, and Jaewoo Kang. Look at the first sentence: Position bias in question answering. arXiv preprint arXiv:2004.14602, 2020.

[2] Xuanhui Wang, Nadav Golbandi, Michael Bendersky, Donald Metzler, and Marc Najork. Position bias estimation for unbiased learning to rank in personal search. In Proceedings of the Eleventh ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, pages 610–618, 2018.

[3] Peiyi Wang, Lei Li, Liang Chen, Dawei Zhu, Binghuai Lin, Yunbo Cao, Qi Liu, Tianyu Liu, and Zhifang Sui. Large Language Models are not Fair Evaluators. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.17926, 2023.

[4] Lianmin Zheng, Wei-Lin Chiang, Ying Sheng, Siyuan Zhuang, Zhanghao Wu, Yonghao Zhuang, Zi Lin, Zhuohan Li, Dacheng Li, Eric. P Xing, Hao Zhang, Joseph E. Gonzalez and Ion Stoica. Judging LLM-as-a-judge with MT-Bench and Chatbot Arena. arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.05685, 2023.

[5] Yang Liu, Dan Iter, Yichong Xu, Shuohang Wang, Ruochen Xu and Chenguang Zhu. G-EVAL: NLG Evaluation using GPT-4 with Better Human Alignment. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.16634, 2023.

[6] Tianyi Zhang, Faisal Ladhak, Esin Durmus, Percy Liang, Kathleen McKeown and Tatsunori B. Hashimoto. Benchmarking Large Language Models for News Summarization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.13848, 2023.

[7] Tim Dettmers, Artidoro Pagnoni, Ari Holtzman, and Luke Zettlemoyer. QLoRA: Efficient Finetuning of Quantized LLMs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.14314. 2023.

[8] Xuechen Li, Tianyi Zhang, Yann Dubois, Rohan Taori, Ishaan Gulrajani, Carlos Guestrin, Percy Liang and Tatsunori B. Hashimoto. AlpacaEval: An Automatic Evaluator of Instruction-following Models. https://github.com/tatsu-lab/alpaca_eval. 2023.

[9] Yann Dubois, Xuechen Li, Rohan Taori, Tianyi Zhang, Ishaan Gulrajani, Jimmy Ba, Carlos Guestrin, Percy Liang, Tatsunori B. Hashimoto. AlpacaFarm: A Simulation Framework for Methods that Learn from Human Feedback. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.14387. 2023.