On Design Choices of Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback

Tuning Large language models (LLMs) with Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF) has shown significant gains over supervised methods. InstructGPT [Ouyang et al., 2022] is capable of hallucinating less, providing chain of thought reasoning, mimicking style/tone, and even appearing more helpful and polite, when instructed to do so. Human preference learning has further been applied to extend LLMs with reference information from the web to support generations (WebGPT) [Nakano et al., 2022] and engage in conversation (ChatGPT). At the same time, the approach alleged to power such models, is seemingly simple. A Reinforcement Learning model trains a policy (initialized as a pretrained LLM) to maximize rewards from a Reward Model (RM) of human preferences. Under the hood, however, the RLHF approach branches out several times based on design choices, into a more complex system of learning. I explore some of those design choices in this post. While the term “Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback” or “RLHF” has been mostly associated with the approach used by OpenAI, there is larger body of prior and recent work on the subject of using RL from human feedback, which is examined here under the same RLHF umbrella.

MDP as a bandit or sequential decision making problem

At the time of writing this article (January 2023), it appears there are two main ways to frame the RLHF approach:

1. As a sequential decision making process:

Using RL with preference learning to optimize existing policies over trajectories has been carried out on Robotics and Atari environments [Christiano et al., 2017], on video game worlds [Abramson et al., 2022], for neural machine translation [Bahdanau et al., 2017], music and computational molecular generation [Jaques et al., 2017], text summarization [Stiennon et al., 2020]*, in Dialog [Jaques et al., 2019], on multiple language tasks in a new GRUE benchmark [Ramamurthy et al., 2022] and other work.

As a sequential decision making process, an MDP is defined over token sequences - where an action is a single token, the state is continuously updated (as a sequence of previous actions), an episode is a sequence of actions until the EOS token or MAX LENGTH, and a dense or sparse reward received at each time step or episode.

2. As a bandit (or more appropriately, a contextual bandit) problem:

Framed as a bandit problem, the action is an entire generation for the input prompt. This is the approach used for training InstructGPT, and other work [Kreutzer et al., 2018; Ziegler et al., 2020; Bai et al., 2022]. From the InstructGPT paper: “The environment is a bandit environment which presents a random customer prompt and expects a response to the prompt. Given the prompt and response, it produces a reward determined by the reward model and ends the episode”.

There isn’t a clear justification (that I have so far found) on which of the two approaches is better. Ramamurthy et al. (2022) compare the two settings on the IMDB dataset, and find that using a token-level MDP with discounted rewards (γ < 1) results in more natural generations with PPO than on the bandit setting. Even in the absence of a thorough study, there are some observations that can be made on this design choice. The first, is that framing a natural language task as a sequential decision process over tokens seems to be more natural or intuitive. Language modeling is an inherently sequential process, and the language modeling objective is framed as a Markov process. But, this could also make it a more difficult problem to solve, requiring learning from and affecting the policy’s original Maximum Likelihood objective on partial sequences. Using a bandit process, on the other hand, avoids the credit assignment problem. Bandit learning may also be closer to SFT than solving for the full RL problem, which may be simpler to learn owing to the use of a strong prior policy. Using dense rewards from a reward model, it may be a stronger signal for optimizing the policy, as compared to the sparse reward in the sequential case. Further, allowing for a fully generated output allows the decoding strategy (greedy versus beam or constrastive search etc.) to interact with the preference learning objective during optimization (instead of its sole use as an inference strategy).

Reward function includes a KL regularization term (KL Control)

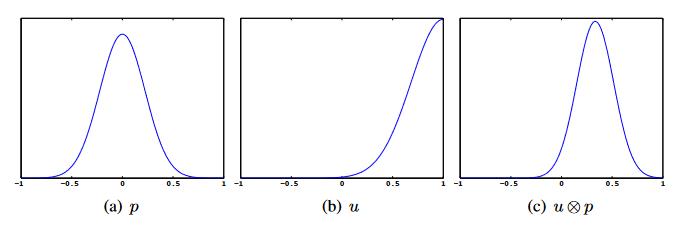

Probability distribution shifted from uncontrolled dynamics (a) to (c) by controller (b). Source: Linearly Solvable Optimal Control, Dvijotham and Todorov, 2012.

The reward function in a standard MDP is considered a part of the environment, and it seems at first sight, a bit strange to add a penalty term that is dependent on the policy. But the idea of adding a KL penalty comes from KL Control [Todorov 2007], a branch of stochastic optimal control (SOC).

The standard definition of an MDP defines a transition dynamics function P(x'|x,u) as the next-state distribution conditioned on the current state and action, and a cost function (or negative of the reward) L(x,u). In KL control, we use an alternate view, that of an uncontrolled (or passive) dynamics shifted by a controller (Dvijotham & Todorov, 2013). Concretely, the original (uncontrolled) distribution of next states, given the current state x, say P0(x'|x), is shifted to P(x'|x) by the controller (inducing an action distribution). To compensate for this choice of different dynamics (P) from the original (P0), a (KL divergence) penalty is imposed on the controller for deviating too far from P0. The cost function is then {L(x,u) + D_KL(P||P0)}. This has the nice property that the KL term acts as an entropy bonus, to favor policies with higher entropy (nice to have on a language generation task).

Such MDPs have been referred to as linearly solvable or LMDPs. Q-learning style updates using a linearized Bellman operator have been used to solve such LMDPs in SOC. Several different choices for the passive/uncontrolled dynamics P0 have led to different algorithms: ψ-Learning (P0 is the policy at the previous iteration) or G-Learning(uniform policy).

Following this framework, in RLHF too, using KL control appears to be a good choice. If we use a strong prior policy as the uncontrolled dynamics, we can nudge it towards a different objective (task or human alignment, for instance), in a controlled way.

In addition to KL control, InstructGPT mixes pretrained gradients with policy gradients during training, a technique that is found to reduce performance regressions (on the original pretrained tasks) over increasing the KL penalty [Ouyang et al., 2022].

Choice of RL algorithm for tuning the policy

Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) has been used in earlier work of learning from human preferences by Christiano et al. (2017) as well as InstructGPT, and Ramamurthy et al. (2022) use a modified PPO algorithm called NLPO. However, several other RL algorithms have also been used in related work. Christiano et al. (2017) use A2C on the MuJoCo tasks, Bahdanau et al. (2017) also use A2C to optimize NMT from BLEU scores, Jaques et al. (2017; 2019) use Batch Constrained Q [Fujimoto et al., 2018a], an offline RL algorithm, modified for discrete actions, and Kreutzer et al. (2018) use the REINFORCE algorithm to train an NMT task. CarperAI’s experiments on Open Instruct use ILQL [Snell et al., 2022], an offline RL algorithm, as an alternative to PPO.

An important consideration for successful RLHF training appears to be the requirement of minimizing the deviation of the policy from its LLM-initialized version. This is so that models are incentived to keep generating natural/realistic sounding text, since most LLMs used with RLFH have been successfully trained for language generation. Jaques et al. (2019) perform experiments that show that KL control (through the KL term in the reward) with Batch Constrained Q-Learning achieves significant gains over the baselines. Without the KL control, models learn to exploit reward generating implausible phrases that maximize the task reward.

With offline RL methods such as Batch Constrained Q, some enhancements are done to improve training, in addition to KL control: the overestimation of Q-values is mitigated by using the lower bound of predicted actions from a Q-network trained with dropout. This achieves an effect similar to Clipped Double Q-Learning [Fujimoto et al., 2018b]. The Q-networks are initialized with pretrained models, to provide a strong prior over the high-dimensional action space (vocabulary).

One thing to note is that PPO already provides a form of KL-control as an approximation of a trust-region method [Schulman et al., 2017]. In practice, a “target-kl” parameter is often used to further ensure small deviations of the policy. Whether the KL penalty in the reward is necessary for learning with existing trust region methods has not (to my knowledge) been explored, or studied through ablation studies. But it is perhaps an extra knob for tightening the policy updates.

Choice of reward model

The two main choices for the reward model in RLHF, are to either frame it as a regression problem, or pairwise preferences. Most of OpenAI’s work on learning from human feedback has used the latter, where a Bradley-Terry model [Bradley and Terry, 1952] is used to estimate score functions from pairwise preferences. On later work, including InstructGPT, more than two choices are presented to the human rater (anywhere between 4 and 9 responses to rank, in the case of InstructGPT), to amortize the cost of reading and understanding the input. The choice of pairwise preferences over Likert scores is based off work done by Li et al. (2019) [Stiennon et al., 2022].

Studies comparing the two methods have been conducted to some extent in prior and recent research. Li et al. (2019) show that a pairwise preference method can detect statistically significant model performance differences to a greater degree than Likert scores, for evaluating dialogue. Kreutzer et al., (2018), conduct a study on the reliability and learnability of cardinal (ratings) and comparative human feedback, on NMT. They find that, while the inter-rater reliability is comparable for the two methods, reward models learn better from cardinal feedback. On the other hand, Wu et al., (2021) find that training a reward model on Likert scores and binary comparison feedback yields similar results on their book summarization task.

The choice of reward model may also be driven by the data collection process. Collecting human pairwise preferences is easier than Likert ratings, and human binary preferences (for example, a thumbs-up/thumbs-down signal) may be used more often in a production environment.

Online or offline learning of the reward model

The reward model itself can be trained in an offline or online manner. In the online setting, the reward model and policy training steps are interleaved iteratively. From the InstructGPT paper: “More comparison data is collected on the current best policy, which is used to train a new RM and then a new policy”. This is also the approach in older OpenAI work by Ziegler et al. (2020). They show that while offline learning works on a simpler stylistic continuation task, on the task of summarization, it often provides inaccurate summaries, which can be avoided by online reward learning. Even though offline learning is more efficient, one of the significant drawbacks is distributional shift.

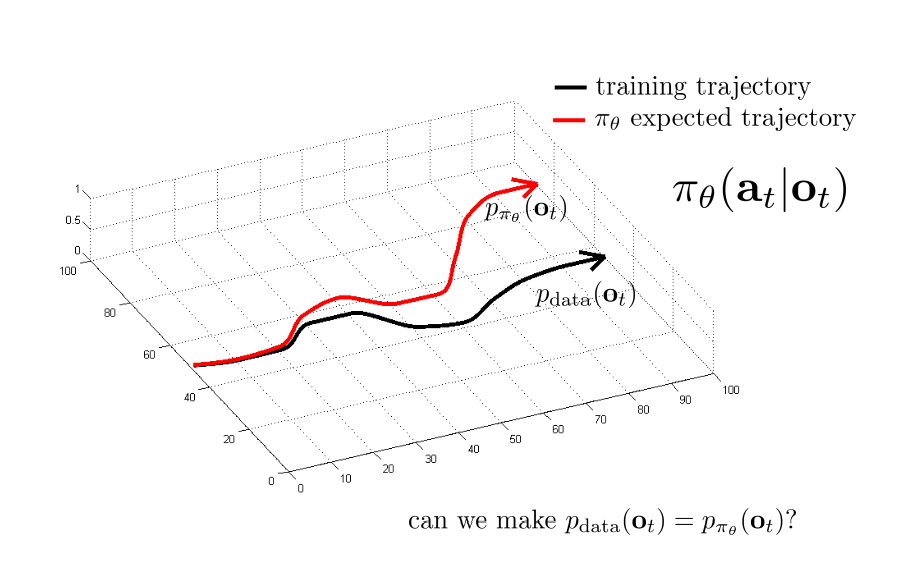

Distributional shift in RL. Source: http://rail.eecs.berkeley.edu/deeprlcourse-fa17/f17docs/lecture_2_behavior_cloning.pdf

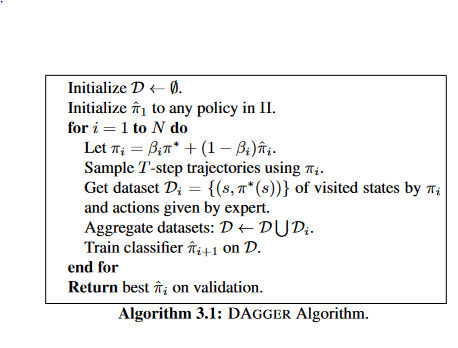

DAgger Algorithm. Source: https://arxiv.org/abs/1011.0686

Distributional shift is a common problem in RL when learning from static/historical data. For instance, a Behavioral Cloning (supervised learning) agent may fail to act optimally when encountering particular states, if these were either missing or present in low proportions in demonstrations during training. Acting sub-optimally can lead to compounding errors, and subsequently, a failed policy. One of the simplest yet effective algorithms to address this issue is called DAgger, short for Dataset Aggregation (Ross et al., 2010). DAgger trains a policy on a demonstrations dataset, runs the policy to obtain observations and queries an expert for optimal actions on those observations, to add to the dataset. This process is repeated until a satisfactory policy is obtained. This process is somewhat similar to the online reward modeling approach of RLHF, with a human as the expert, providing a reward signal of the performed action instead of the action itself. There is a large body of work in mitigating distributional shift in RL, that may be applicable to RLHF as future improvements.

In Summary

The word on the street is that RLHF is difficult to get working, and may have some undesired side effects, for instance, alignment tax, mode collapse. While this post discusses the main design choices, plenty other tips and tricks have been used to get RLHF to work. Finally, RLHF is not the only approach to optimize models from human feedback. Other approaches such as TAMER (Training an Agent Manually via Evaluative Reinforcement) and COACH (COrrective Advice Communicated by Humans) exist that could be applied to the language modeling task.

References

[1] Ouyang et al. 2022. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback

[2] Nakano et al. 2022. WebGPT: Browser-assisted question-answering with human feedback

[3] Christiano et al. 2017. Deep reinforcement learning from human preferences

[4] Bahdanau et al. 2017. An Actor-Critic Algorithm for Sequence Prediction

[6] Stiennon et al. 2022. Learning to summarize from human feedback

[7] Wu et al. 2021. Recursively Summarizing Books with Human Feedback

[12] Ziegler et al. 2020. Fine-Tuning Language Models from Human Preferences

[13] Fujimoto et al. 2018a. Off-policy deep reinforcement learning without exploration

[14] Fujimoto et al. 2018b. Addressing function approximation error in actor-critic methods

[15] K. Dvijotham and E. Todorov. 2012. Linearly Solvable Optimal Control

[16] E. Todorov. 2007. Linearly-solvable Markov decision problems

[17] Schulman et al. 2017. Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms

[21] Snell et al. 2022. Offline RL for Natural Language Generation with Implicit Language Q Learning

* Based on what is reported in the paper, it is listed as using the sequential approach, although most OpenAI models have been trained using the bandit environment setup.

If you use this post in your research, please consider citing as follows:

@article{amanda2023rlhf,

title={On Design Choices of Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback},

author={Amanda Dsouza},

year={2023}

}