Reward Leakage in Imitation Learning

Reward Leakage in Imitation Learning

At the heart of Reinforcement Learning, is learning from evaluative feedback. This is typically specified in terms of a reward or cost function. In the absence of a reward function, an agent can learn from an expert (policy or demonstrations), either in a supervised manner (Behavioral Cloning), by first recovering a reward function that is optimal for the demonstrations (Inverse RL), or by learning to generate expert-like trajectories (Adversarial Imitation Learning). Collectively, these methods are considered Imitation Learning. A natural assumption in Imitation Learning is that the environment provides no feedback to the agent. However, the manner in which most RL environments and sometimes RL libraries are implemented currently, leaves room for leakage of reward information. This problem of reward leakage can be generally observed in the sparse reward setting, and is described below.

Variable and fixed length episodes

Consider a gridworld, where the agent, starting at some position, must navigate to a goal state. An episode terminates when the goal is reached, or some maximum number of timesteps are taken. For instance, in OpenAI Gym, this is usually represented by the done flag, and additional info buffer. Whatever the reason for termination, when an episode terminates, the done flag is set to true. Even without the knowledge of rewards, we can infer from this information. Shorter episodes in this environment are optimal, while longer ones are not.

The info buffer can also leak reward information. Gym, for instance, passes TimeLimit.truncated flag, that specifies if the episode terminated due to a terminating state, or a timeout. An example of the popular Stable Baselines 3 shows how the rollout buffer of an on-policy algorithm uses this information to process rewards of terminal states. Gym-robotics environments record a is_success flag in the info buffer, when the desired goal is achieved. In general, such information related to the episode can be exploited by a biased reward function.

# Handle timeout by bootstraping with value function

# see GitHub issue #633

for idx, done in enumerate(dones):

if (

done

and infos[idx].get("terminal_observation") is not None

and infos[idx].get("TimeLimit.truncated", False)

):

terminal_obs = self.policy.obs_to_tensor(infos[idx]["terminal_observation"])[0]

with th.no_grad():

terminal_value = self.policy.predict_values(terminal_obs)[0]

rewards[idx] += self.gamma * terminal_value

Reward function bias

In Adversarial Imitiation Learning algorithms, such as Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning (GAIL) and its variants, it is not uncommon to use different forms of the reward/cost functions, based on the environment. A reward function log D(s,a) encourages the agent to terminate quickly by providing negative rewards; good for maze/grid environments where the goal is to complete the task in the fewest timesteps possible. On the other hand, a reward function -log(1-D(s,a)) acts as a survival bonus, encouraging the agent to stay in the environment to maximize its return; good for environments such as Pong or Breakout.

These aren’t the only settings. Consider a gridworld environment with additonal negative rewards or penalties, for instance, the toy frozen lake environment. In this case, either choice of reward function does not bias towards the desired behavior. Consequently, such environments may be less influenced by the choice of the reward sign. Still other environments, may be inherently more complex, for which this reward bias is not sufficient for learning. Nevertheless, it is common practice to use one of these rewards forms as priors in the imitation learning paradigm.

The problem of variable length episodes has been well described here. And the effects of reward bias have been illustrated by Kostrikov et al, in which they show that GAIL with a biased reward can learn a preference for expert like trajectories only under certain values of the discount factor, deriving which depends heavily on the underlying MDP.

In this article, we demonstrate how a pathological reward function can learn even in more complex settings of learning from visual observations on several gridworld and 3D tasks, and show much better performance than the baseline GAILfO (GAIL from observations).

Experiment Details

Generative Adversarial Imitation Learning, Ho and Ermon, 2016

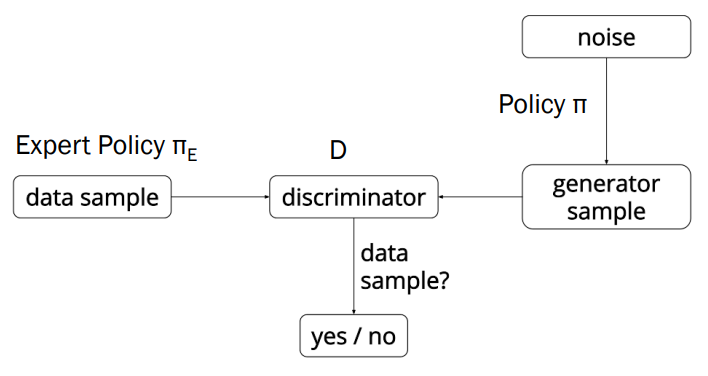

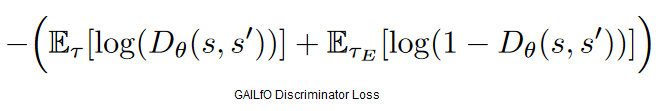

GAIL uses adversarial learning to jointly train a discriminator and generator on a state-action occupancy matching objective. The discriminator loss, is similar to the GAN discriminator loss, optimizing a dual objective; i.e. increasing the cost of non-expert demonstrations, while decreasing the cost of expert demonstrations.

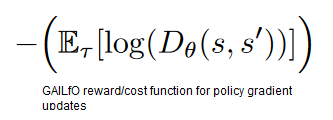

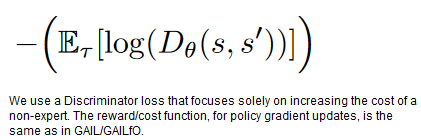

We create a pathological loss function, by removing the loss component that optimizes the cost of expert demonstrations. In this case, the expert demonstrations are no longer used for training, and the result is a network that predicts a constant negative reward for all input observations. Minimizing the loss during training results in reducing the penalty given to the agent.

Theoretically, any constant (and unchanged during training) reward function, should still let the agent learn the optimal behaviour in sparse reward environments with reward leakage (since this is equivalent to scaling of the reward). Indeed, Kostrikov et al show that using a reward of 0.5 for every state-action pair on the Hopper environment, can achieve rewards of around 1000. However, in our experiments with several choices of constant rewards, we do not find this to be true. It could be a combination of different factors, such as complexity of learning from visual observations, insufficient tuning, choice of discount factor etc. Nevertheless, the “reward function” we use provides no distinguishing signal to the agent. Learning then occurs, due to leakage from the terminal/non-terminal information and optimizing shorter trajectories due to the negative rewards through the biased reward function.

Experiment Results

On sparse reward tasks

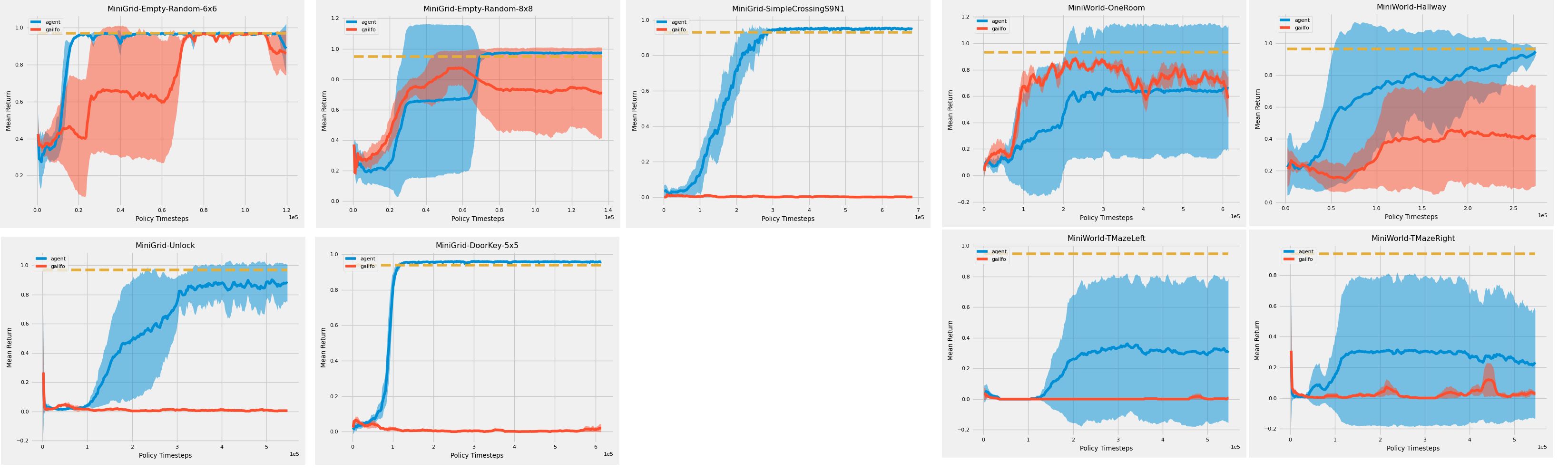

We conduct experiments using GAILfO as the baseline, and our pathological loss, which we refer to as “agent”, since it only uses agent data in the loss computation. To test the sparse reward setting, we use the Minigrid (minimalistic gridworlds), and Miniworld (minimalistic 3D environment, similar to DM Lab) tasks. Some of these environment require the agent to simply reach the end state, while others require it to take some action, such as picking up a key, in order to achieve the goal of opening a door. We use pixel observations, with no action information, and the reward function log D(s,a) . We use stacked observations for Miniworld, since it is a more difficult environment than gridworld. As an example, an expert policy for the TMazeRight or TMazeLeft environments, on average, takes 60 timesteps to reach the goal at the end of a T shaped maze. In all these tasks, there are no negative absorbing states.

Even though both methods have access to the leaked rewards, the “agent” loss can quickly learn the task, while GAILfO fails. This is likely due GAILfO’s attempts at matching the expert trajectories, which interferes with the leaked reward signal.

Mean Reward + 95% confidence levels on Minigrid, and Miniworld environments, using pixel observations (egocentric observations in case of Miniworld), over 3 seeds.

Mean Reward + 95% confidence levels on Minigrid, and Miniworld environments, using pixel observations (egocentric observations in case of Miniworld), over 3 seeds.

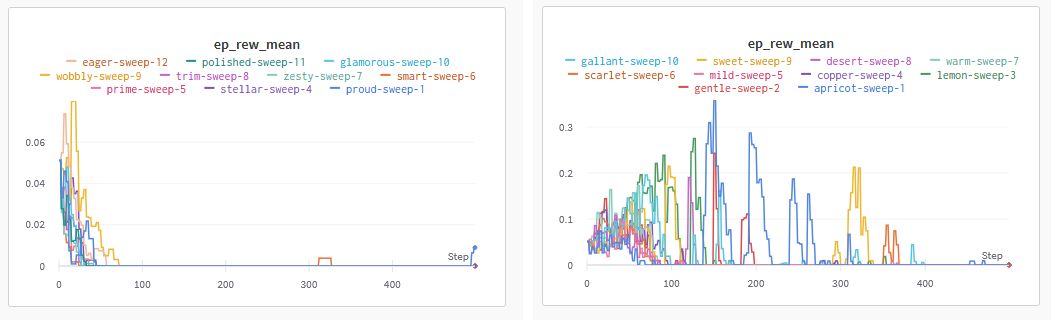

While leaky rewards worked well in sparse reward tasks with only positive absorbing states, they may be less sensitive to environments with both positive and negative absorbing states. For instance, the Lava gap gridworld task has both positive and negative absorbing states. An agent must reach the goal state, while avoiding the lava. In this case, the agent loss does not learn, since no single biased reward function allows it to terminate quickly while avoiding the lava states.

W&B sweeps on the Lava environment.

W&B sweeps on the Lava environment.

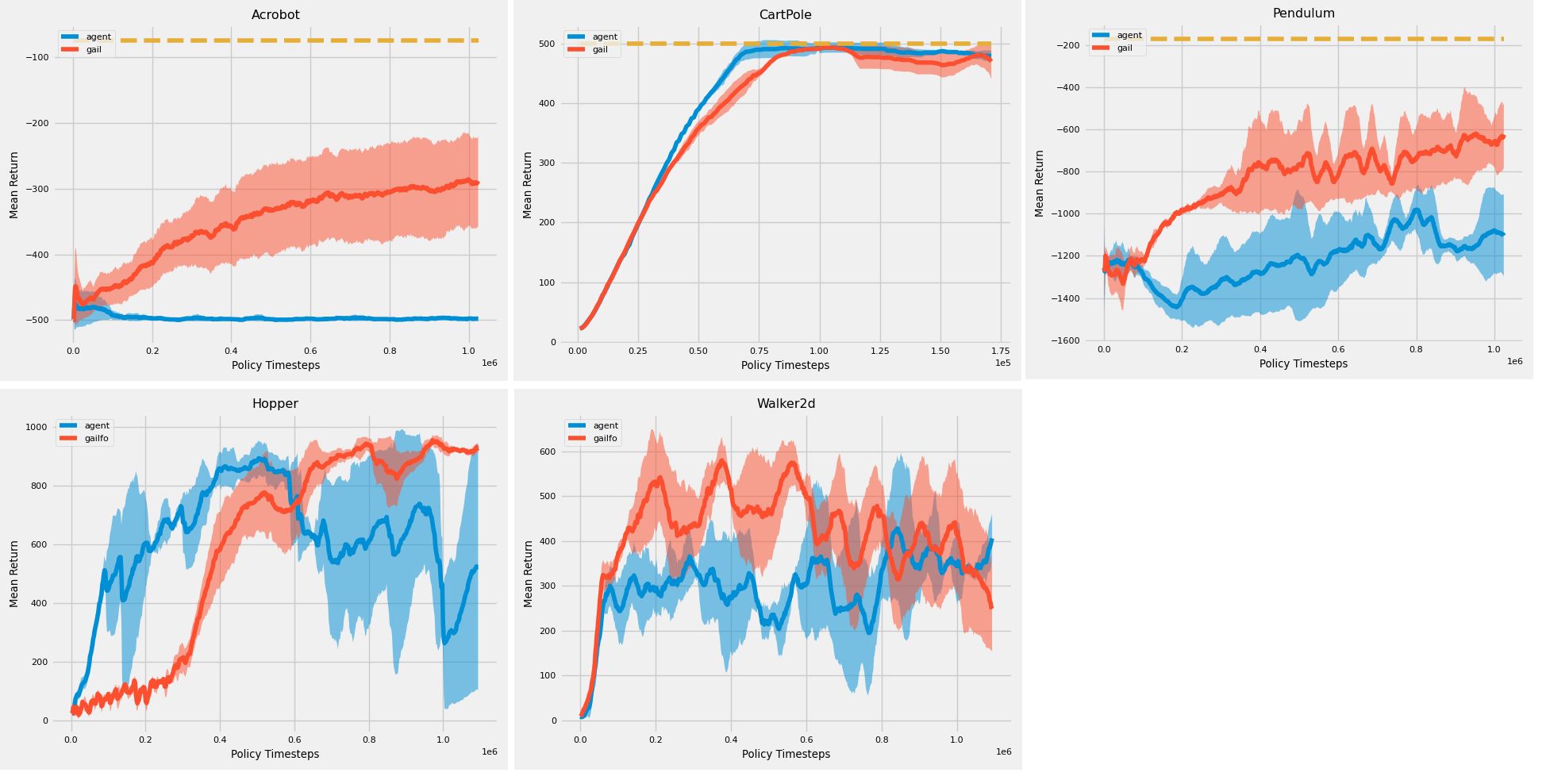

On dense reward tasks

Similar to the Lava case, we find that dense reward tasks are also less sensitive to the reward leakage. Since the two cases of terminating an episode - either by executing the maximum number of steps, or reaching a goal - require the agent to stay in the environment for the full length of the episode, these two cases are indistinguishable, and therefore, difficult to exploit. For the dense reward settings, we test using stacked pixel observations, on Mujoco tasks (Walker and Hopper) and using (state-action) demonstrations, on classic control tasks (CartPole, Acrobot and Pendulum). The reward function used in this case is -log (1-D(s,a)).

Results on dense reward tasks: Classic Control tasks (CartPole, Acrobot and Pendulum) using demonstrations (LfD) and Mujoco using pixel observations, over 3 seeds.

Results on dense reward tasks: Classic Control tasks (CartPole, Acrobot and Pendulum) using demonstrations (LfD) and Mujoco using pixel observations, over 3 seeds.

Correcting reward leakage

Kostrikov et al plug the reward leakage by use of an additional absorbing state, for which rewards must also be learnt by the IL algorithm. This is done by augmenting the state vector with an additional bit, that is set to 1 if the state is absorbing. For an absorbing state, all other bits are set to zero. Orsini et al additionally add a transition from the absorbing state to itself, with zero action. Minigrid, and Miniworld environments, include a “done” action, in which case, no transitions may be necessary. In this case, GAIL has the burden of learning the best action (“done”) in the absorbing state. Adding an absorbing dimension may be difficult to implement or train, with pixel observations.

The seals project provides fixed horizon versions of some Gym environments. For instance, a fixed horizon CartPole always returns done=False and info={}. However, the action space is left unchanged. When an agent achieves the goal, it is unclear what the optimal action should be. In a similar manner, on the Mujoco environments that have early termination, a correction terminate_when_unhealthy=False is applied.

The problem of reward leakage can inadvertently occur in even in more complex environments. And several of the current impelementations exhibit variable length episodes, including those that are popularly used in Imitation Learning research. It is unclear, how well known this issue of reward leakage is, but having found only limited literature on this topic, it may need to be highlighted more, especially as Adversarial IL and Deep RL gains more popularity.

If you use this post in your research, please consider citing as follows:

@article{amanda2022rewardleakage,

title={Reward Leakage in Imitation Learning},

author={Amanda Dsouza},

year={2022}

}