Examining Gradients of Generalization in RL

Generalization studies in scientific fields

One of the hallmarks of any learning system is generalization. Loosely defined as the capability to learn general concepts from specific training examples, it is something that comes very naturally to human beings. From only a few examples, human beings are capable of applying the learning to a wide spectrum of similar and sometimes unrelated tasks. Moreover, how (and how much) we generalize can have significant effects on well being [29]. It is no wonder then, that much effort has been spent in understanding it, in various fields of science. In Neuroscience, studies of memory representations [1] and instabilities [2] that support generalization, environmental complexity that governs the degree of generalization in spatial movement [3] have tried to advance our understanding of why generalization occurs. In Psychology, generalization to different stimuli (for example, fear) has been studied extensively, and has tried to advance our understanding of how generalization occurs.

In our quest to create intelligent agents, where intelligence has been, so far, benchmarked by human cognitive abilities, one of the fundamental goals of Machine Learning is generalization. To that end, extensive research has been carried out in defining generalization [4] [5] [6], and towards building generalizable agents and models [7] [8] [9]. In Reinforcement Learning, several studies of the problem [10] [11] [12] have been conducted, new benchmarks proposed [13] [14] [15], and algorithms developed.

However, (from a limited search) there is little literature of generalization in both Machine Learning and Reinforcement Learning, that strongly draws from Psychology. In an attempt to bridge that gap, I take a look at one important topic, that has been extensively studied in Psychology, namely “Gradients of Generalization”, applying it to (a small subset of) RL agents. In this small sample study, and under specific learning conditions, I find evidence that generalization in RL agents exhibits the same form of (stretched exponential) decay. If such a universal law is found to exist, we could perhaps transfer some of the well studied findings in animal psychology (such as peak shifts [16], avoidance learning [17]) to artificial agents, for instance to construct intentional generalization behavior. This could potentially have implications in fields of AI Safety and Robustness. Further, perhaps gradients of generalization could be used to determine generalization guarantees, similar to scaling laws.

Conditioned reflexes

We start by briefly reviewing some of the early work in classic and operant conditioning in Psychology. In 1927, Pavlov, in his seminal experiments on classic conditioning [18], showed that a neutral stimulus (bell sound) associated with an unconditioned stimulus (food) was used to generate a conditioned response (salivating at the bell sound) in dogs. This experiment is well known today. In what is perhaps less well known, subsequent experiments by Pavlov showed that conditioned responses were found to occur on test stimuli, that were different, but similar (in pitch, for instance) to the original conditioned (training) stimulus. This led to numerous experiments [19], analyzing “gradients of stimulus generalization”, measuring the degree of learned responses to distances between the test and original training stimulus.

Univeral law of Generalization

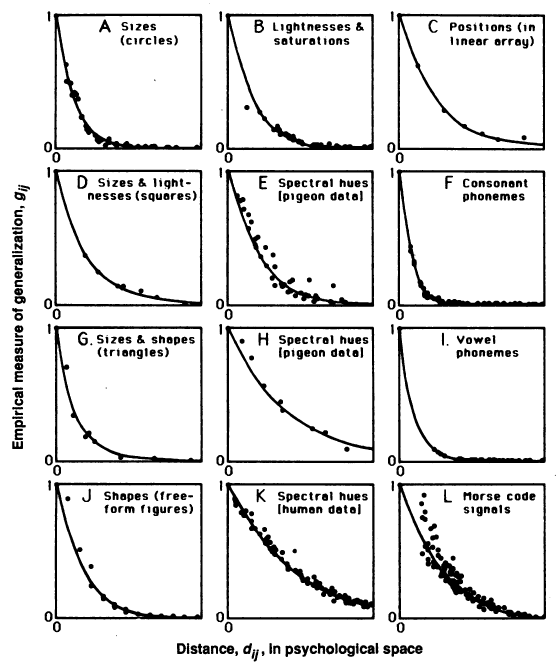

Figure 1. 12 Gradients of Generalization following exponential decay curves, Roger Shepard, 1987 (Source: [20])

In 1987, following this work, Roger Shepard showed that there exists a universal law of generalization [20], which is the focus of this post. According to the law, the probability to which a learned response to a specific stimulus generalizes to another different stimulus depends on the “distance” between the stimuli and follows an exponential decay with this distance (Figure 1). Importantly, this distance measure is not in physical space, but one in psychological space.

Previous attempts at measuring “gradients of generalization” used physical measures of differences between stimuli, (for example, frequency / size / wavelengths). Even though physical differences lead to an overall decrease of generalization with increasing distance, the decrease is not necessarily monotonic nor invariant. Shepard, therefore, sought to find a monotonic and invariant function, whose inverse transformed the observed generalization data into distances in some “psychological” space. (Psychological space can be understood as equivalent to latent space in Machine Learning). Shepard found that the exponential decrease in this “psychological space” follows universally among different stimuli, sensory modalities, and across multiple species.

Mathematical formulation

Shepard proposed the following method to uncover the universal law: For generalization data G, that is first normalized by g_ij = [(p_ij . p_ji) / (p_ii . p_jj)]^(1/2) (where p_ij is the probability of generalization on stimulus j, when trained on stimulus i), on a set of stimuli S (s+ as the original trained stimuli, and s- as any other test stimuli), and a distance metric d, we want to recover a function f as,

This can be done by using Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS) [21]. NMDS is a dimensionality reduction method that finds a lower dimensional space which preserves the ordering of the similarity in data. It models the similarity in the data as distances in metric space. On an n X n symmetric matrix of (normalized) generalization measures g_ij, NMDS finds a lower dimensional space in some k (k « n) dimensions. Points in this space can now represent distances between the original points and are invariant to the underlying experiment data. Then, using some metric distance (Shepard shows that Euclidean and Manhattan distances work well for stimuli data), one can uncover the universal law.

Experiment details

Figure 2. Experiments on modified environments of (a) MiniGrid Random 6x6 and 8x8 grids (b) MiniWorld-Hallway (c) Lunar Lander (d) CartPole

Figure 2. Experiments on modified environments of (a) MiniGrid Random 6x6 and 8x8 grids (b) MiniWorld-Hallway (c) Lunar Lander (d) CartPole

Shepard’s experiments were conducted on humans and animals on a wide range of stimuli such as colors attributes (lightness, saturation), sizes, spectral hues, phonemes, shapes, and Morse code signals. Subsequent studies conducted experiments on distance and direction stimuli [22]. In order to replicate the work, I conduct experiments on three simple environments, OpenAI Gym [23] Classic Control, MiniGrid [24] and MiniWorld [25]. The aim is to examine what the gradients of generalization of RL agents look like for different “stimuli” (interpreted as factors or parameters of the agent or environment), and to test the hypothesis if RL agents follow a universal law of generalization. In order to do this, I vary the following stimuli in separate experiments: hue angle, saturation, orientation, distance of the goal object and length of agent.

MiniGrid random grids (of sizes 6x6 and 8x8) are simple grid layouts with the agent initialized to a random position. In order to avoid overfitting of the agent to the goal position, the goal position is also randomized. MiniWorld is a Minimalistic 3D environment with egocentric view observations and discrete actions. In the Hallway environment, a box (or object) is placed at the far end of the hallway, with the agent at the other end, with the goal of the agent to pick up the box. On these environments, I vary the hue angle (9 discrete hues from red to green) and saturation (from 0% to 100%) of the goal tile or box. Pixel observations are used on these experiments. An additional experiment on Hallway varies the orientation of a large key as the goal (from 0 to 180 degrees), with grayscale image observations to avoid the agent overfitting to the color attributes of the goal. Lastly on Classic Control, I use Cartpole with varying lengths of poles, and Lunar Lander, with varying positions of the lander to the landing pad, in the range [-5,5]. In order to control for difficulty of the Lunar Lander task at different landing pad positions, the terrain is made smooth everywhere, and the lander starts exactly above the landing pad, in all cases, similar to the default setting.

PPO is used as the learning algorithm, trained over 5 random seeds, and each policy is evaluated over 100 episodes. A CNN network (Stable Baselines 3 [30] NatureCNN with architecture used in [31]) is used to learn from visual observation data. To learn a latent space based on the original distances, I use NMDS as proposed in the original paper, on the generalization data, with Euclidean distance in the resultant latent space to compute the generalization curves. The code is implemented using Stable Baselines 3 and Scikit-Learn [32].

Experiment results

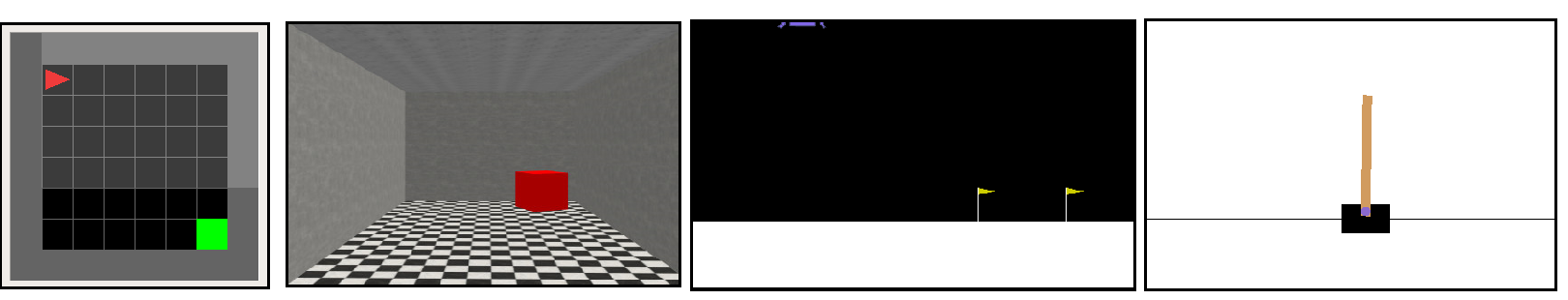

Figure 3. Degree of Generalization with latent distance on Hue and Saturation in MiniGrid 6x6, 8x8 and MiniWorld-Hallway environments, averaged over 5 random seeds, and evaluated over 100 episodes. Plots exhibit stretched exponential decays with increasing distance in latent space.

Figure 3. Degree of Generalization with latent distance on Hue and Saturation in MiniGrid 6x6, 8x8 and MiniWorld-Hallway environments, averaged over 5 random seeds, and evaluated over 100 episodes. Plots exhibit stretched exponential decays with increasing distance in latent space.

In experiments involving hue and saturation (Figure 3), the degree of generalization to latent distance exhibits a stretched exponential curve. (A stretched exponential uses a fractional power law in the exponential function). This implies that to some extent an agent will generalize to varying stimuli, before sharply dropping off. Both hue and saturation can be considered to be spurious correlation features, that are irrelevant to the task. They are also independent along the spectrum they are varied over. For instance, having a red or green box as the object to pick up should not render the problem more or less difficult. As Shepard points out, for stimuli such as color, the generalization is symmetric, since they do not possess any preferred axes in their psychological space (since the dimensions do not correspond to real world independent attributes). In the language of Psychology, these stimuli can be considered as “neutral” stimuli, which do not affect the behavior of the conditioned stimulus. It appears that this is an important distinction to recover the exponential decay in RL agents.

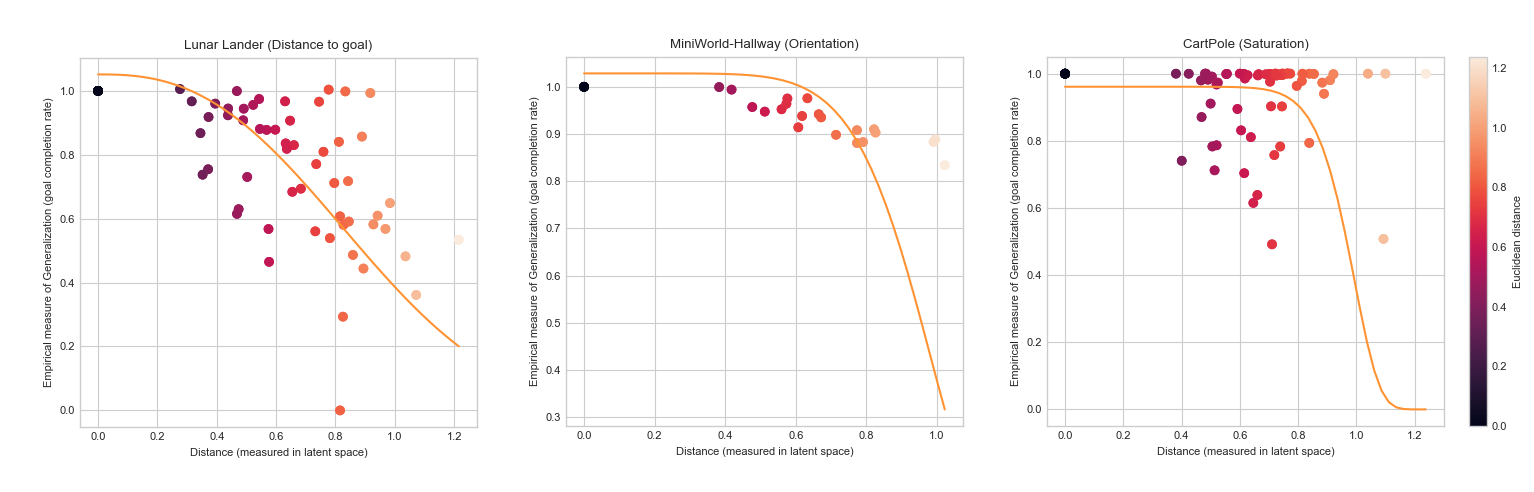

Figure 4. Degree of Generalization with (a) latent distance on Distance of lander to landing pad, (b) Orientation of key, and (c) CartPole lengths, averaged over 5 random seeds, and evaluated over 100 episodes.

Figure 4. Degree of Generalization with (a) latent distance on Distance of lander to landing pad, (b) Orientation of key, and (c) CartPole lengths, averaged over 5 random seeds, and evaluated over 100 episodes.

In the case of lunar lander experiments (Figure 4a), using the distance (between the agent and landing pad) stimulus, I expected to observe a similar generalization curve. All things being equal, one would expect to see generalization sharply drop off, the further the landing pad from the agent’s starting position. And further, that this would be invariant to the direction of generalization (left -> right versus right -> left). However, the results are somewhat surprising. It appears that the agent is able to generalize more favorably in one direction, than the other. (Recall that the terrain has been made smooth throughout and wind effect is set to false in the default lander settings). The only other explanation could be the dynamics that cause it to behave this way. Specifically the turbulence power applied to the lander may be biased towards one direction. However, I was unable to find the source of this bias.

In the case of orientation experiments (Figure 4b), we find that the graph decays more gradually. This implies, that the agent is able to generalize better over the different orientations. This may be due to the limited variation in the orientation stimulus. Using a CNN network also allows for some rotational invariance. Using other distance metrics such as absolute cosine distances or Manhattan distance, as Shepard proposed, does not recover an exponential curve. Given that some orientations (less occluded) ought to be more easily learnable than others, I am uncertain if a stretched exponential can be recovered. In a similar manner, it is not possible to recover an exponential generalization curve on cartpole lengths (Figure 4c) due to the asymmetric nature of the stimulus, i.e. it is easier to generalize from longer to shorter poles than vice-versa.

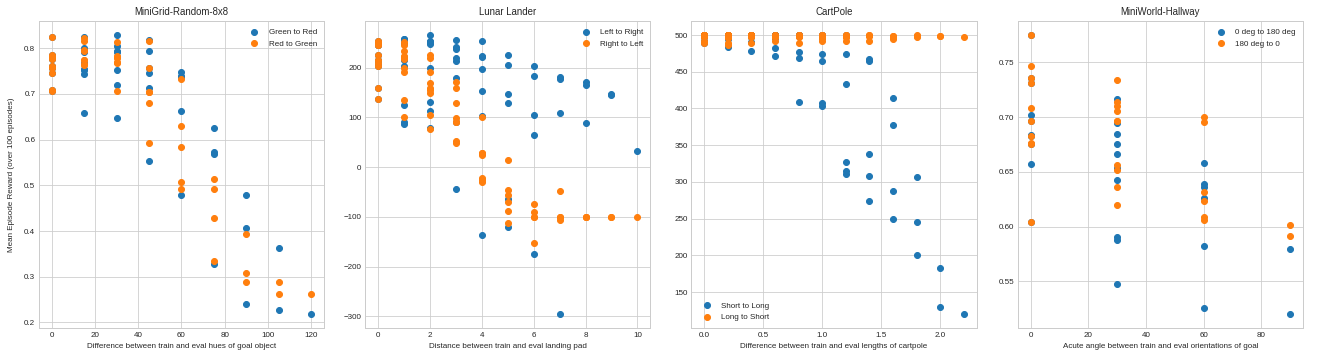

Note that in the case of both orientation and cartpole lengths, the stimuli are not neutral, but instead, change the task (in complexity or otherwise). This can be visualized better in Figure 5, on true distances. In which case, it may not be possible to recover the exponential curves using the Euclidean or Manhattan distance. This has been also elucidated in [26], as challenges to the universal law, concerning asymmetry of the (properties of) psychological stimuli.

Figure 5. Degree of generalization with true distance. (a) Hue on MiniGrid-6x6 grid as a reference of stretched exponential decay (b) Distance of lunar lander to landing pad appears to generalize better left-to-right, than right-to-left. (c) Cartpole lengths unsurprisingly exhibit better generalization from long to short pole lengths, than vice-versa (d) Difference of acute angles of key (goal) in Hallway environment exhibit a linear decay with a larger variance.

Figure 5. Degree of generalization with true distance. (a) Hue on MiniGrid-6x6 grid as a reference of stretched exponential decay (b) Distance of lunar lander to landing pad appears to generalize better left-to-right, than right-to-left. (c) Cartpole lengths unsurprisingly exhibit better generalization from long to short pole lengths, than vice-versa (d) Difference of acute angles of key (goal) in Hallway environment exhibit a linear decay with a larger variance.

Discussion and critiques of universal law

While the experiments I have conducted replicating Shepard’s work on RL agents are more of a proof of concept (or curiosity), on some neutral stimuli, there is some evidence that generalization may decay, in a universal manner, following a (stretched) exponential curve. When stimuli are not neutral but affect the learning capacity, we can no longer expect the same decay patterns. Of course, more experiments are necessary to substantiate any such claim.

Finally, there have been studies challenging aspects of the universal law itself. Shepard showed that the distance metric used in uncovering the universal law differed based on the nature of stimuli. In order to alleviate this dependence, [26] proposed a more abstract information metric (expressed in terms of Koglomorov complexity) that can work universally on arbitrary complex stimuli. (Several other critiques of the law are expanded on in the paper which we leave to the interested reader). [27] suggests that rate distortion theory provides an explanation for the universal law, and that any efficient system operating under constraints of limited capacity (biological or artificial) naturally recovers the exponential decay. Further, that Shepard’s law is a specific case of the law dictated by rate distortion. [28] shows that the exponential decay is due to the properties (shift and stretch invariance) of the perceptual scale of stimuli, and anything beyond that, such the type of transformation (NMDS) or distance metric (Koglomorov complexity) is merely superfluous.

Despite these critiques, an important takeaway from these experiments is that there are some fundamental similarities between how biological and artificial agents learn, that allow for similar generalization patterns. Studying gradients of generalization in artificial agents could be useful, to understand or apply some of the broad research that has been conducted on psychological studies of this phenomenon.

If you use this post in your research, please consider citing as follows:

@article{amanda2022gradientsofgen,

title={Examining Gradients of Generalization in RL},

author={Amanda Dsouza},

year={2022}

}

References

[2] Edwin M. Robertson. Memory instability as a gateway to generalization

[3] Kurt A. Thoroughman and Jordan A. Taylor. Rapid Reshaping of Human Motor Generalization

[4] L G. Valiant. A Theory of the Learnable

[5] Kenji Kawaguchi, Leslie Pack Kaelbling, Yoshua Bengio. Generalization in Deep Learning

[6] David Haussler. Probably Approximately Correct Learning

[7] Robert E. Schapire. The Boosting Approach to Machine Learning: An Overview

[8] Scott Reed et al. A Generalist Agent

[9] Rich Caruana. Multitask Learning

[10] Robert Kirk et al. A Survey of Generalisation in Deep Reinforcement Learning

[11] Chiyuan Zhang et al. A Study on Overfitting in Deep Reinforcement Learning

[12] Charles Packer et al. Assessing Generalization in Deep Reinforcement Learning

[13] Alex Nichol et al. Gotta Learn Fast: A New Benchmark for Generalization in RL.

[14] Karl Cobbe et al. Leveraging Procedural Generation to Benchmark Reinforcement Learning

[16] Edward P. Kardas. Generalization and Peak Shift

[17] Agnes Norbury, Trevor W Robbins, Ben Seymour. Value generalization in human avoidance learning

[19] Norman Guttman and Harry I. Kalish. Discriminability and stimulus generalization

[20] Roger N. Shepard. Toward a Universal Law of Generalization for Psychological Science

[21] J. B. Kruskal. Nonmetric multidimensional scaling: A numerical method

[22] Ken Cheng. Shepard’s Universal Law Supported by Honeybees in Spatial Generalization

[23] Greg Brockman et al. OpenAI Gym

[24] Chevalier-Boisvert et al. Minimalistic Gridworld Environment for OpenAI Gym

[25] Maxime Chevalier-Boisvert. MiniWorld: Minimalistic 3D Environment for RL & Robotics Research

[26] Nick Chater and Paul M. B. Vitanyi. The generalized universal law of generalization

[30] Antonin Raffin et al. Stable-Baselines3: Reliable Reinforcement Learning Implementations

[31] Volodymyr Mnih et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning.

[32] F. Pedregosa et al. Scikit-learn: Machine Learning in Python